|

This essay introduces one of the two volumes that launched the Media in Transiton book series in spring 2003. Introduction, Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), edited by David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins |

|

|

Against Apocalypse A change

has taken place in the human mind…. The conviction is already

not very far from being universal, that the times are pregnant

with change; and that [our era]…will be known to posterity

as the era of one of the greatest revolutions…in the human

mind, and in the whole constitution of human society….

The first of the leading peculiarities of the present age is,

that it is an age of transition. Set aside

the nineteenth-century tonalities, and this passage could belong

to our own era. Its apocalyptic rhetoric and its self-conscious

awareness of change closely mirror the discourse of the so-called

digital revolution. Mill is responding to the vast transformations

that define the nascent Victorian age-the introduction of the

railroads, the emergence of powerful new manufacturing technologies,

fundamental alterations in the economic and political order

of English society, the expansion of a global empire.2

The advent of the computer also has generated visions of apocalyptic

transformation. In one recurring scenario, we stand on the cusp

of a technological utopia where emerging communications systems

foster participatory democracy and give all citizens access

to an infinite range of commercial services, audio-visual texts,

job training, libraries, and universities. The reverse of such

optimism envisions an on-line culture of chaos, instability

and greed in which pornographic images corrupt children and

challenge parental authority; information is commodified and

available only to those who can pay; political discourse is

balkanized by extremist special interests; and human experience

itself is "denatured" or displaced by the virtual

reality of the computer screen.3 Similar utopian and dystopian visions were a notable feature of earlier moments of cultural and technological transition-the advent of the printing press, the development of still photography, the mass media of the nineteenth century, the telegraph, the telephone, the motion picture, broadcast television.4 In these and other instances of media in transition, the actual relations between emerging technologies and their ancestor systems proved to be more complex, often more congenial, and always less suddenly disruptive than was dreamt of in the apocalyptic philosophies that heralded their appearance.5 Across a range of examples, including the introduction of the compass in the middle ages, the telegraph, radio, satellite television, software, and digital music, Debora L. Spar argues that technological change follows a cycle of innovation and experimentation, commercialization and diffusion, creative anarchy and institutionalization.6 During each phase, discourses proclaiming radical change may locate stress points where emerging forms of wealth and power appear to threaten established institutions. In our current

moment of conceptual uncertainty and technological transition,

there is an urgent need for a pragmatic, historically informed

perspective that maps a sensible middle ground between the euphoria

and the panic surrounding new media, a perspective that aims

to understand the place of economic, political, legal, social

and cultural institutions in mediating and partly shaping technological

change.7 The essays

in this book represent an effort to achieve such an understanding

of emerging communication technologies. At once skeptical and

moderate, they conceive media change as an accretive, gradual

process, challenging the idea that new technologies displace

older systems with decisive suddenness.8 Some contemporary

doomsayers warn that the digital revolution signals the death

of the book and the end of cinema. In such simplified models

of media in transition, the new system essentially obliterates

its predecessors, taking on the functions of its ancestors,

and consigning the older form to the museum and the ash heap.

The science fiction writer Bruce Sterling, for example, has

established a website devoted to "dead media," old

technologies that have outlived their usefulness.9

But this seems a narrowly technical idea of media. Specific

delivery technologies (the eight-track cassette, say, or the

wax cylinder) may become moribund; but the medium of recorded

sound survives. As many studies of older and recent periods

attest, the emergence of new media sets in motion a complicated,

unpredictable process in which established and infant systems

may co-exist for an extended period or in which older media

may develop new functions and find new audiences as the emerging

technology begins to occupy the cultural space of its ancestors.

Thus, traditional oral forms and practices outlast the advent

of writing and even the culture of print; the illuminated manuscript

survives for a time into the Gutenberg era; theater and the

novel co-exist with movies and television; radio reinvents itself

after TV displaces its entertainment and news-reporting role

in the national culture. Moreover, in many cases apparently

competing media may strengthen or reinforce one another, as

books inspire movies which in turn stimulate renewed book sales,

as television serves as a virtual museum for the history of

film, as newspapers,, television and movies today are discovering

a variety of strategies for extending and redefining themselves

on the World Wide Web. As these

instances suggest, to focus exclusively on competition or tension

between media systems may impair our recognition of significant

hybrid or collaborative forms that often emerge during times

of media transition. For example, the Bayeux tapestry (c. 1067-1077)

combined both text and images, and was explicated in spoken

sermons-a multimedia bridge between the oral culture of the

peasants and the learned culture of the monasteries.10

Or consider the nineteenth-century practice of the painted photograph,

an aberrant oddity to recent generations who take for granted

the representational accuracy of mechanical reproduction in

relation to images drawn by hand. In its day, though, the painted

photograph-correcting photography's monochromy and its tendency

to fade over time-was understood within the centuries-old tradition

of portrait painting.11

As a final example, contemporary experiments in story-telling

are crossing and combining several media, exploiting computer

games or web-based environments that offer immersive and interactive

experiences that mobilize our familiarity with traditional narrative

genres drawn from books, movies and television. Current discussion about media convergence often implies a singular process with a fixed end point: All media will converge; the problem is simply to predict which media conglomerate or which specific delivery system will emerge triumphant.12 But if we understand media convergence as a process instead of a static termination, then we can recognize that such convergences occur regularly in the history of communications and that they are especially likely to occur when an emerging technology has temporarily destabilized the relations among existing media. On this view, convergence can be understood as a way to bridge or join old and new technologies, formats and audiences. Such cross-media joinings and borrowings may feel disruptive if we assume that each medium has a defined range of characteristics or predetermined mission. Medium-specific approaches risk simplifying technological change to a zero-sum game in which one medium gains at the expense of its rivals. A less reductive, comparative approach would recognize the complex synergies that always prevail among media systems, particularly during periods shaped by the birth of a new medium of expression. Self-conscious

Media As our contemporary

experience demonstrates, a crucial, distinguishing feature of

periods of media change is an acute self-consciousness. McLuhan

argues that "media are often put out before they are thought

out."13 Yet the

introduction of a new technology always seems to provoke thoughtfulness,

reflection, and self-examination in the culture seeking to absorb

it. Sometimes this self-awareness takes the form of a reassessment

of established media forms, whose basic elements may now achieve

a new visibility, may become a source of historical research

and renewed theoretical speculation. What is felt to be endangered

and precarious becomes more visible and more highly valued.

In our time the most decisive instance of this process is the

multi-national scholarship devoted to the history of the book.14

As William Mitchell's suggestive essay in this volume implies,

the promise or threat of electronic books engenders a renewed

consciousness of the rare and durable qualities of printed books;

not least of which is their portability and their stability

across time. Compared to the short life of various electronic

and digital systems, including the operating systems of computers,

the printed book is a "platform" reassuringly stable

and secure. Moreover,

a deep and even consuming self-consciousness is often a central

aspect of emerging media themselves. Aware of their novelty,

they engage in a process of self-discovery that seeks to define

and foreground the apparently unique attributes that distinguish

them from existing media forms. Consider this definitive instance of the profound self-reflexiveness of which a new medium is capable. In the third chapter of Part II of Don Quixote (Part I, 1605; Part II, 1615) the hero consults with his squire Sancho Panza and the learned scholar Sampson Carrasco, who is to report on the mysterious publication of Part I of the novel. This volume has appeared as if "by magic art," and much to Quixote's discomfort, even while

The complex

unease suggested here—Quixote's

doubts about his chivalric enterprise encouraging the defensive

suspicion that Moors are untrustworthy—continues through

the whole of this chapter and the next, and makes a comic and

aesthetically complex contrast with Sancho's confident, even

aggressive loquaciousness. Repeatedly interrupting his learned

betters, Sancho directs our attention toward those elements

of their past adventures that are least Quixotic and most congruent

with the pragmatic earthiness of his sense of the world. Some

readers, Carrasco says, "would have been glad if the authors

had left out a few of the countless beatings" endured by

Quixote and his squire. The hero agrees, of course, but his

squire does not. "That's where the truth of the story comes

in," Sancho insists. This wonderful mixture of comic energy

and philosophic/ aesthetic argument is further enriched when

Carrasco inquires into an apparent inconsistency in the history.

"I don't know how to answer that," said Sancho. "All

I can say is that perhaps the history-writer was wrong, or it

may have been an error of the printer's." This characteristic

moment is, of course, a disconcertingly bold way of reminding

us that the book we are reading is a physical object, a commodity

produced and perhaps altered by technicians who know nothing

of Dulcinea and probably do not care to know. It is appropriate,

even deeply significant that Quixote actually visits a printing

plant late in Part II, where he studies the physical processes

by which books are made and where he discourses on the difficulties

of translation, finally seeing a proofreader at work on the

spurious second part of the Quixote itself. This insistence

on the limits of the book we hold in our hands, and especially

Cervantes' recurring tactic of allowing the novel's several

narrators to intrude into Quixote's story and to interrupt it,

deflects attention toward what has been called the drama of

the telling, a drama concerned not with the protagonist's adventures

themselves but with the problems and difficulties of writing

about them. The Quixote is, among other things, then, a book

about the making of books and the nature of story telling. Its

daring self-reflexive comedy is also a systematic exploration

of the special properties of the infant medium of the novel.15 As the example

of Don Quixote implies, often the most powerful explorations

of the features of a new medium occur in comedy.16

Many forms of self-reflexiveness are inherently skeptical, self-mocking,

hostile to pretension. The early television comedian Ernie Kovacs

regularly toyed with audience's expectations about the visual

bias of television, creating anarchic comedy in absurd synchronizations

of classical music with mundane activities (such as cracking

open eggs to the 1812 Overture). In one segment, Kovacs

places a portable radio in front of the camera while the radio

announcer's voice describes a woman in a revealing bathing suit.

Here as elsewhere Kovacs seems to wink at the audience, as if

to suggest that there are some things best enjoyed on television.

In another skit, Kovacs makes the soundtrack visible on screen,

exploring the possibility that even audio may have an arresting

visual component. Kovacs assumes that his viewers actively watch

television, fixated on the novelty of the image, in contrast

to some more recent television producers who have assumed that

spectators divide their attention between television and other

household tasks. Early movies,

of course, are another immensely fertile space for experimentation.

Many early motion picture exhibitors, for example, used the

camera and projection technology to dramatize the shift from

still to moving pictures-either opening with a still image before

setting it into motion or projecting footage backwards to reverse

the sequence of action we've just seen, so that a wall that

had been destroyed as we watched is now magically rebuilt before

our eyes. As Tom Gunning has written, early cinema "directly

solicits spectator attention, inciting visual curiosity, and

supplying pleasure through exciting spectacle."17

This cinema emphasized its "visibility," often calling

attention to its grand illusion by toying with the possibility

of transgressing the boundary between the audience and the world

projected on the screen. A similar degree of self-consciousness

emerged in the early sound era. Al Jolson's proclamation in

The Jazz Singer—"You ain't heard nothing yet!"—dramatically

emphasizes the spoken word, but not nearly so powerfully as

the sudden shift back to the conventions of silent cinema when

his father, the cantor, appears and demands "Silence!"18 In some instances the earliest phase of a medium's life may be its most artistically rich , as pioneering artists enjoy a freedom to experiment that may be constrained by the conventions and routines imposed when production methods are established. It is widely argued, for example, that the most creative era in the history of the American comic strip was its first decades, a period in which artists controlled the layout of their own pages. Winsor McCay's Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumherland contained bold, surrealistic images of topsy-turvy worlds and of figures stretched imaginatively out of proportion. These strips also manipulated the shape and proportion of the frame itself and even created frames within a frame, such that characters inside the comic panel would read picture books that in turn contained panels. Another early comic artist, George Herriman, drew characters who interacted with the panels below them and created images that burst free of the confines of the frame, releasing havoc across the page. One of Herriman's early strips included a second row of panels depicting the experiences of mice beneath the floorboards of the depicted space. When comic strips came to be distributed by national syndicates, rigid formulas were imposed to insure that the panels could be slotted into any newspaper page. Since the comic strip had to have a preset number of panels in a fixed relationship to each other, artists ceased to explore the complex formal properties of this popular medium.19 Imitation, Discovery, Remediation If emerging

media are often experimental and self-reflexive, they are also

inevitably and centrally imitative, rooted in the past, in the

practices, formats and deep assumptions of their predecessors.

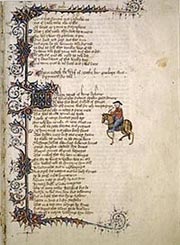

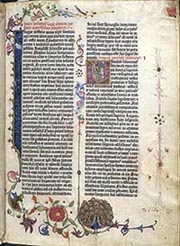

The first printed book, The Gutenberg Bible (c. 1455), contains

a stunning emblem of this unvarying law of media evolution.

For in what seems today a perverse failure to exploit the defining

feature of print as against scribal texts, Gutenberg's landmark

book has been elaborately and painstakingly illustrated by hand-artisans

in the established style of the medieval illuminated manuscript.

The striking if perverse continuity thus created was dramatized

in a recent exhibition by the Huntington Library, which juxtaposed

a copy of the Gutenberg, open to a richly illuminated page,

with the famous Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer's Canterbury

Tales (c. 1400), also beautifully illustrated by a scribal

artist (see fig. 1.1). The print revolution-the power to reproduce

a large number of identical texts-is latent but invisible here,

suppressed or ignored by an impulse of continuity, a need to

experience this new medium under the aspect of established ways

of reverence and of art.20 Such holdovers of old practices and assumptions have shaped the introduction of many new technologies and may be best illustrated by examples from outside the realm of media history. The physical design of early automobiles, as many have noted, embodied a version of the same continuity principle. Why do the first cars look like horse-drawn buggies, many of them preserving for as long as twenty years such nostalgic and nonfunctional features as dashboard whip sockets? Nothing in the technology of the internal combustion engine requires these forms of obeisance to older models of transportation. But, of course, invention itself is shaped and constrained by history, by inherited forms of thought and experience. Yet another

instructive version of the power of traditional practices to

channel our understanding and use of new technologies is available

in Harold L. Platt's The Electric City, an account of

the emergence of the electric utility industry in Chicago at

the turn of the twentieth century.21

The key transition here is not technological so much as cognitive

or psychological, for according to this fascinating history,

a sustained campaign of political lobbying and consumer marketing

was needed to persuade home-owners and businesses to abandon

their individual power-generating systems and purchase their

energy from a central station or power plant. The idea that

energy supplies could be "outsourced" more efficiently

and economically than self-generation ran counter to centuries

of practice in which homes, farms, mills, businesses and factories

maintained their own systems of energy production. Does that

history of an earlier turning from reliance on privately owned,

home-based systems to centralized power-nodes anticipate contemporary

shifts, already discernible in much corporate computer use and

among many individual web surfers, from autonomous desk-top

computing to forms of data-sharing and outsourcing? These examples—Gutenberg,

the horseless buggy, the electric city—and many others

we've not mentioned illustrate how inherited forms and traditions

limit and inhibit, at least at the start, a full understanding

of the intrinsic or unique potential of emerging technologies.

But this continuity principle must not be conceived as merely

or essentially an impediment to the development of new media.

In Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin's influential formulation,

all media engage in a complex and ongoing process of "remediation,"

in which the tactics, styles and content of rival media are

rehearsed, displayed, mimicked, extended, critiqued.22

We should be clear that not all forms of self-consciousness

are profound-some are simply trivial novelties, and not all

forms of continuity are constraining-some may quicken latent

possibilities in the emerging medium, while others, more simply,

may aim to help confused or disoriented consumers make the transition

into the unfamiliar terrain opened by the new medium. Self-reflexivity

and imitation are contrasting aspects of the same process by

which the new medium maps its emergent properties and defines

a space for itself in relation to its ancestors. The novel,

for example, is born as an amalgam of older forms, which it

explicitly invokes and imitates-the romance, the picaresque

tale, certain forms of religious narrative such as Puritan autobiography,

and various forms of journalism and historical writing. At first

it combines these elements haphazardly and crudely. Then, nourished

by an enlarging audience that makes novel writing profitable,

this central story-form of the age of print begins to distinguish

itself clearly from its ancestors, to combine its inherited

elements more harmoniously, and to exploit the possibilities

for narrative that are uniquely available in the medium of print.23 As many

have argued, something of the same principle can be seen in

the history of the movies, which begin in a borrowing and restaging

of styles, formats and performances taken from a range of older

media such as theater, still photography, visual art, and prose

fiction. A second powerful source for early cinema was such

public attractions as carnivals, the circus, amusement parks,

vaudeville. Some film historians have argued that the defining

attribute of the birth of the movies was the contention between

a self-reflexive and populist "cinema of attractions,"

(to use Tom Gunning's helpful term) and a more respectable,

even middle-class tendency toward narrative as inspired by theater

and print.24 Such perspectives remind

us that the forms achieved by a "mature" medium do

not comprise some perfect fulfillment of its intrinsic potential

but represent instead both a range of limited possibilities

and promises unexplored, roads not taken. Recent scholarship

has even suggested that the movies assumed and more fully achieved

some of the prime ambitions of its ancestors. The time of the

birth of a new medium, these histories remind us, is often ripe

with anticipation. Vanessa R. Schwartz, for example, suggests

that fin de siecle Paris was awash in visual spectacles

such as panoramas and wax museums offering an immersive reproduction

of the world that would be realized truly only by the movies.25

Lauren Rabinovitz has studied how the cinema took shape in the

context of amusement-park attractions.26

Erik Barnouw has shown how magicians prepared the ground for

the movies by introducing its technical marvels to the public.27

And in some cases, these expectations were frustrated by the

new medium: William Uricchio suggests, for example, that some

early critics were disappointed when cinema failed to realize

their expectation of simultaneous transmission of distance events.28

The story is not merely one of imitation and self-discovery,

then, but something more complicated. If movies were in some

sense replicating earlier media, those ancestor systems were

also aiming imperfectly and incompletely to satisfy expectations

that would ultimately give rise to the cinema. As we suggested

earlier and as these examples indicate, medium-specific perspectives

may limit our understanding of the ways in which media interact,

shift and collude with one another. The evolution of new communications

systems is always immensely complicated by the rivalry of competing

media and by the economic structures that shape and support

them. In some cases, such as broadcasting where the same networks

dominated both radio and television, existing institutions simply

expand to absorb and appropriate emerging technologies.29

In other cases, as in the competition between nickelodeons and

legitimate theaters, emerging media may offer opportunities

for investment and upward mobility prohibited by the rigid infrastructure

of established systems. To comprehend the aesthetics of transition, we must resist notions of media purity, recognizing that each medium is touched by and in turn touches its neighbors and rivals. And we must also reject static definitions of media, resisting the idea that a communications system may adhere to a definitive form once the initial process of experimentation and innovation yields to institutionalization and standardization. In fact, as the history of cinema shows, decisive changes follow upon improvements in technology (such as the advent of sound, the development of lighter, more mobile cameras and more sensitive film stock, the introduction of digital special effects and editing systems); and seismic shifts in the very nature of film, in its relation to its audience and its society, occur with the birth of television. No

Elegies for Gutenberg30 As the foregoing

implies, these processes of imitation, self-discovery, remediation

and transformation are recurring and inevitable, part of the

way in which cultures define and renew themselves. Old media

rarely die; their original functions are adapted and absorbed

by newer media; and they themselves may mutate into new cultural

niches and new purposes: The process of media transition is

always a mix of tradition and innovation, always declaring for

evolution, not revolution. We citizens and scholars do well to recognize such continuity principles and to remain skeptical of apocalyptic projections of gloom or glory. Is the printed book obsolete? Almost certainly not. Will many of its noblest and most valuable functions-most forms of scholarship and research, dictionaries, encyclopedias-migrate to the computer? Yes, absolutely. This has already begun to happen. But—as the poet Milton says—nothing is here for tears. The crucial continuity involves not books but language itself. Language is migratory across communications media and will endure. Notes 1. Rpt. in George Levine, ed., The Emergence of Victorian Consciousness: The Spirit of the Age (New York: Free Press, 1967), 71. 2. The nineteenth century as the site of the emergence of a new information culture and as a parallel to our own age of transitions has received extensive consideration in recent years. See, for example, James W. Carey and John J. Quirk, "The Mythos of the Electronic Revolution," in James W. Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society (New York: Routledge, 1989); Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-Line Pioneers (Berkeley: Berkeley Publications, 1999); Thomas Richards, The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire (London: Verso, 1996); Doron Swade, The Difference Engine: Charles Babbage and the Quest to Build the First Computer (New York: Viking, 2001 ); Daniel R. Hendrick, When Information Came of Age: Technologies of Knowledge in the Age of Reason and Revolution, 1700-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); James W. Cortada, Before the Computer (Trenton: Princeton University Press, 2000). For a fictional response to this same topic, see William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, The Difference Engine (New York: Spectra, 1992). 3. On the competing visions of the computer, see, for example, Mark Stefik, Internet Dreams: Archetypes, Myths and Metaphors (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). 4. On the rise of nineteenth-century technologies, see, in addition to texts cited above, Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electronic Communications in the Late Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990); Lisa Gitelman, Scripts, Grooves and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in Edison's Era (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000); Daniel Czitron, Media and the American Mind: From Morse to McLuhan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983); Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983); Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railroad Journey: The Industrialization of Time in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); Friedrich A. Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999); Friedrich A. Kittler, Discourse Networks, 1800/1900 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992); David E. Nye, The Technological Sublime (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996); David E. Nye, Electrifying America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992); Claude S. Fischer, America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); M. Susan Barger and William B. White, The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000); Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992). 5. Much of what follows has been inspired by Raymond Williams, Television: Technology and Cultural Form (New York: Schocken, 1977). There is also a growing body of literature on media transitions or information revolutions. See, for example, Brian Wilson, Media Technology and Society: From the Telegraph to the Internet (New York: Routledge, 1998); Irving Fang, A History of Mass Communications: Six Information Revolutions (New York: Focal, 1997); Alfred D. Chandler and James W Cortada, eds., A Nation Transformed By Information: How Information Has Shaped the United States from Colonial Times to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); Wiebe Bijker, Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995); Michael E. Hobart and Zachary S. Schiffman, Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Computer Revolution (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000); Neil Rhodes and Jonathan Sawday, eds., The Renaissance Computer: Knowledge Technology in the First Age of Print (New York: Routledge, 2000); Steven Johnson, Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate (New York: Basic, 1999); Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001). 6. Debora L. Spar, Ruling the Waves: Cycles of Discovery, Chaos, and Wealth from the Compass to the Internet (New York: Harcourt, 2001). 7. One possible model for such a discourse is represented by the technological realists. See, for example, <http://www.technorealism.org/>. 8. Paul Duguid, "Material Matters: Aspects of the Past and Futurology of the Book" in The Future of the Book, ed. Geoffrey Nunberg (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). For other significant work on the impact of digital media on the culture of print, see Roger Chartier, Forms and Meanings: Texts Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995); James Joseph O'Donnell, Avatars of the Word: From Papyrus to Cyberspace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000); John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2000); David M. Levy, Scrolling Forward: Making Sense of Documents in The Digital Age (New York: Arcade, 2001 ); Sven Birkerts, Tolstoy's Dictaphone: Technology and the Muse (St. Paul: Graywolf Press, 1996); Janet Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999). 9. Bruce Sterling, Dead Media Project, <http://www.deadmedia.org>. 10. See Wolfgang Grape, The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph (Munich: Prestel, 1994); Richard Gameson, ed., The Study of the Bayeux Tapestry (Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 1997); Suzanne Lewis, The Rhetoric of Power in the Bayeux Tapestry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999). 11. Heinz K. Henisch, The Painted Photograph 1839-1914: Origins, Techniques, Aspirations (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996). 12. For a fuller discussion of media convergence, see Henry Jenkins, "Convergence? I Diverge," Technology Review (June 2001); "Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars?: Digital Cinema, Media Convergence, and Participatory Culture," in this volume; Thomas Elsaesser and Kay Hoffman eds., Cinema Futures: Cain, Abel, or Cabel (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1998); Dan Harries, ed., The New Media Book (London: BFI, 2002). 13. Marshall McLuhan, "The Playboy Interview," in The Essential McLuhan, ed. Eric McLuhan and Frank Zingrone (New York: Harper Collins, 1996). 14. See, for example, David Hall, Cultures of Print: Essays on the History of the Book (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996); Robert Darnton, Literary Underground of the Old Regime (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985); Robert Darnton, The Forbidden Best Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996); Roger Chartier, Order of Books (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994); Lucien Febvre, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800 (London: Verso, 1997); Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980); Frederick G. Kilgour, The Evolution of the Book (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Natalie Zemon Davis, Society and Culture in Early Modern France: Eight Essays (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977). 15. This material draws on David Thorburn, "Fiction and Imagination in Don Quixote," Partisan Review XLII, no. 3 (1975): 431-443. See also Robert Alter, Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975). 16. On comic self-reflexivity, see J. Hoberman, Vulgar Modernism: Writings on Movies and Other Media (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991). 17. Tom Gunning, "The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant Garde" in Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Adam Barker (London: BFI, 1990). For other influential discussions of early cinema (beyond those found in Elsaesser and Barker), see Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); Charles Musser, Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and The Edison Manufacturing Company (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991); Charlie Keil, Early American Cinema in Transition: Story; Style and Filmmaking, 1907-1913 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002); Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theater to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); John L. Fell, Film Before Griffith (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983); Yuri Tsivian, Early Cinema in Russia and Its Cultural Reception (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). 18. For discussion of the coming of sound, see Donald Crafton, Talkies: America Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926-1931 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Henry Jenkins, What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991 ). 19. On the richness of early comics, see Bill Waterson, "The Cheapening of the Comics," The Comics Journal (October 27, 1989). On the emergence of comics, Robert C. Harvey, The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994); John Canemaker, Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1987); Richard Marschall, ed., Dreams and Nightmares: The Fantastic Art of Winsor McCay (Westlake Village, CA: Fantagraphics Books, 1988); David Kunzle, History of the Comic Strip (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973). 20. Scott D. N. Cook, "Technological Revolutions and the Gutenberg Myth," in Mark Stefik, Internet Dreams: Archetypes, Myths and Metaphors (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996): "The same standards of craftsmanship and aesthetics associated with manuscripts were applied to printed books for at least two generations beyond the Gutenberg Bible" (71). 21. Harold L. Platt, The Electric City: Energy and Growth Of the Chicago Area, 1880-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991). 22. Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000). 23. Ian P Watt, The Rise of the Novel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957); Michael McKeon, The Origins of the English Novel, 1600-1740 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988); Nancy Armstrong, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1995); Ruth Perry, Women, Letters, and the Novel (New York: AMS Press, 1980). This paragraph and later sections of this introduction draw extensively on David Thorburn, "Television As an Aesthetic Medium," Critical Studies in Mass Communication 4 (1987): 168-169. 24. Tom Gunning, D. W. Griffith and The Origins of American Narrative Film (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994); David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, Classical Hollywood Cinema (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Ben Singer, Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001 ); Roberta Pearson, Eloquent Gestures: The Transformation of Performance Style in the Griffith Biograph Films (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson, Reframing Culture (Trenton: Princeton University Press, 1993). 25. Vanessa R. Schwartz, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siecle Paris (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). 26. Rabinovitz, For the Love of Pleasure: Women, Movies, and Culture in Turn-of the-Century Chicago (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998). 27. Erik Barnouw, The Magician and the Cinema (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1981). 28. William Uricchio, "Technologies of Time," in Allegories of Communication: Intermedial Concerns from Cinema to the Digital, ed. J. Olsson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). 29. On the evolution of radio broadcasting, see Susan Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting 1899-1922 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997); Michele Hilmes, Radio Reader: Essays in the Cultural History of Radio (New York: Routledge, 2001); Susan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1994). For considerations of cultural responses to the introduction of television, see Lynn Spigel, Make Room For TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1992); Lynn Spigel, Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001); Cecelia Tichi, Electronic Hearth: Creating an American Television Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992); Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence From Telegraphy to Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000); Anna McCarthy, Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001). 30. Sven Birkerts's The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age (New York: Fawcett, 1995) seeks to defend the culture of the book against the emerging digital culture.

|